Obama, Joshua, Immigration, Barrios and Favelas,

The Parrot Speaks Out on the State of

the

OK, so it’s a peculiar combination; but bear with me.

I had been terrified that the American electorate was not going to be capable of doing it, but when, on 4 November 2008, the voters were actually able to elect an extremely intelligent, thoughtful, Black man—from a northern city, no less—as our 44th President, my sense of belief in the American people was profoundly strengthened, and my hope for the democratic process in our country was enormously restored.

It is not hard to understand why I was worried that

Americans would be unable to elect an African-American to be their

President: racism in

Why it seemed so unlikely that intelligence and thoughtfulness would be qualities of an electable candidate is best summed up by Paul Krugman’s description of the very heretofore successful Republican anti-intellectual, anti-thoughtfulness strategy in his excellent Op-Ed piece in The New York Times on 7 August 2008:

know-nothingism

— the insistence that there are simple, brute-force, instant-gratification

answers to every problem, and that there’s something effeminate and weak about

anyone who suggests otherwise — has become the core of Republican policy and

political strategy. The party’s de facto slogan has become: “Real men don’t

think things through.” (www.nytimes.com/2008/08/08/opinion/08krugman.html?_r=1&scp=21&sq=paul+krugman+column&st=nyt&oref=slogin)

And this strategy has, over the past decades, become a frighteningly successful one—culminating in the presidency of George W. Bush.

It has become dangerous

for any politician to appear to be too thoughtful about issues, no less to talk

about them in any depth or with any level of sophistication. To succeed with the American public, ideas

have needed to be reduced to the most simplistic of sound bites—the shorter and

more sloganistic the better. I had trouble even watching the debates,

since—aside from what the Republican side was putting forth—even Barack Obama

had to be careful not to appear too intellectual or answer questions in too

sophisticated or deep a way. Meaningful

political discourse about real issues has all but disappeared from American

politics But the fact that any party

would have the shamelessly cynical audacity to put a Sarah Palin

forward to be their candidate for Vice President of the United States was

staggering: three decades ago no one

would have dreamt of doing such a

thing, even if it seemed to be clearly advantageous to winning—and, three

decades ago, there was no way that it would have been. Americans had always wanted to look up to

their leaders, to be in awe of the intellect, experience, and power of their

leaders—not to want their leaders to be people they would be “comfortable

having a beer with.” It is also

reasonable to think that part of this dreadful state of affairs is related to a

frighteningly profound decline in education in

But the American people did succeed in electing just such a person. I was so moved by it, I sent around a quote from Ethan Bronner’s piece from The New York Times (q.v., www.RLRubens.com/bronner.htm):

From far away, this is how it

looks: There is a country out there where tens of millions of white Christians,

voting freely, select as their leader a black man of modest origin, the son of

a Muslim. There is a place on Earth — call it

And I was so moved by that, I rather uncharacteristically added,

“Hazak hazak v’nithazek”: “Be strong, be strong. And let us strengthen one another” (or, sometimes translated idiomatically as, “Be strong and of good courage”) [Joshua 1:6] It is God’s charge to Joshua, and it is what Jews say at the end of the yearly cycle of reading the Torah, as they return to Genesis for the beginning of the reading of the next cycle. There is something that has ended, and there is a hopeful new beginning. Let us hope we have the strength and courage to realize its possibilities.

More than one of my recipients responded that they were

shocked to hear me quoting anything religious, because they knew how troubled I

have been over the past decades by the stupidity that has been applied to

religion, and the stupidity that has been reflected in so much of religious

thought. Three decades ago, no political party in the

Nevertheless, this Hebrew saying was what had sprung to my mind. As I said in that email, it had very much to do with its having been something that was traditionally said at the end of a cycle and the affirmation of returning to a new beginning (and, I suppose it contributes for me that the end in question was the book of Deuteronomy and the parts of the Pentateuch of which I had always been least fond, and the new cycle takes us to Genesis—the book that generations of my students [from a former life of mine] could tell you was always my favorite Jewish subject to teach). It also must have something to do with the exhortation to be strong—something very much called for in our moving forward into this particular future—and with the idea of communally strengthening each other. But it also cannot be accidental that it is from the book of Joshua. (Well, it is not exactly or completely from the book of Joshua, although it certainly is a reference thereto and is at least partially therefrom. For those who may be interested in such details, I include in the NOTES at the end of this email a list of corrections about what I had written about this idea and its origins, q.v., infra.)

When I sent around that email, I received an email back from

a friend at The New Yorker, who said it was

interesting that I had quoted Joshua,

and that I should be on the lookout for the article David Remnick had coming out in their

next issue. My curiosity thus peaked, I gave some more thought to Joshua. Joshua was the leader who, after the death of

Moses (who had led the Jews out of Egypt, but then wandered with them for 40

years in the wilderness), actually led the Jews into the Promised Land; but

this eponymous leader’s book in the Bible is actually a rather fanciful account of that bit of

history: it portrays their entry into

Canaan as that of a mighty army conquering quickly and systematically the

territory before it (best know from the story of Joshua’s conquest of Jericho),

while everything that is known about the actual historical reality was

radically different from that. The far more historical account of that very

same process is to be found in the book of Judges,

in which the Jews actually enter

This thought thoroughly took me aback. As a participant in of the Urban

Age (a program is centered at the London School of Economics and funded

by the Alfred Herrhausen Society [the international

forum of Deutsche Bank] and which sponsors a series of world-wide conferences,

dedicated to studying the problems and issues facing cities in the 21st century

and creating dialogues designed to find solutions q.v.,

my  write-up

of the 2007 UA Mumbai conference

and other Urban Age

events), we have been looking this year specifically at South America—and I

am about to travel to São Paulo, Brazil, for the UA conference there at the

beginning of December. What is so typical of the development of

informal cities in South America—the slums or barrios or favelas

there (like the barrio of Petare, in Caracas, pictured at the left in a photograph by

my friend and UA participant, Alfredo Brillembourg [click here for higher

resolution image] or the favela of Paraisópolis in São Paulo [click here for an image of the

poverty of this favela encroaching right up against

the incredible wealth of the established part of the city])—is that the poor,

often the immigrants to the city, build their dwellings up the sides of the

undesirable, steep hills, occupying the high land not wanted by the rich, more

established inhabitants who live on the more desirable, safer, flat lands

below. It is a process known in Spanish

as “La cuidad

informal se come a la colina,” “The informal city

eats the hill.” Like the Jews entering

write-up

of the 2007 UA Mumbai conference

and other Urban Age

events), we have been looking this year specifically at South America—and I

am about to travel to São Paulo, Brazil, for the UA conference there at the

beginning of December. What is so typical of the development of

informal cities in South America—the slums or barrios or favelas

there (like the barrio of Petare, in Caracas, pictured at the left in a photograph by

my friend and UA participant, Alfredo Brillembourg [click here for higher

resolution image] or the favela of Paraisópolis in São Paulo [click here for an image of the

poverty of this favela encroaching right up against

the incredible wealth of the established part of the city])—is that the poor,

often the immigrants to the city, build their dwellings up the sides of the

undesirable, steep hills, occupying the high land not wanted by the rich, more

established inhabitants who live on the more desirable, safer, flat lands

below. It is a process known in Spanish

as “La cuidad

informal se come a la colina,” “The informal city

eats the hill.” Like the Jews entering

Immigration, it turns out, has been on my mind for many

reasons. Anyone who studies cities and

the dynamisms of their growth patterns is well aware the crucial importance and

power of immigration. Essentially, major

cosmopolitan cities do not exist without immigration—it is the engine that

drives their growth and prosperity, whether it is immigration from foreign countries

or immigration into the cities from the rural outlands. It is extremely striking that over the past

decades

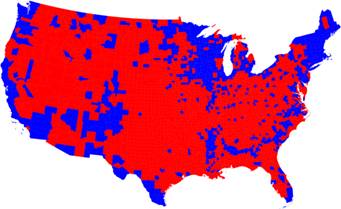

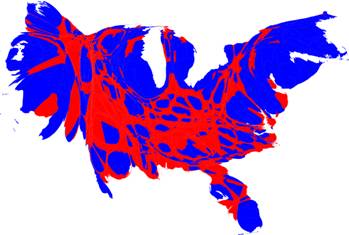

The voting divide in the

The majority of the counties voting Democratic (in blue) are the urban counties, and the vast areas of red are mostly rural. It is why that even in an election in which the Democrats won by an extremely comfortable margin, it looks like the country was largely Republican. Mark Newman’s clever use of cartograms (maps in which the sizes of states—or, in this case, counties—are rescaled according to their population, i.e., they are drawn with size proportional not to their acreage but to the number of their inhabitants) gives a much more accurate view of what the election returns were like. In the one below, one can readily see how the blue counties, when drawn by population size rather than geographic area, were as decisive as they turned out to be:

For months I had been on a rant about the decline of the

Some weeks into this rant, I began to realize that this

“American spirit” so peculiarly to our history is actually an immigrant

spirit! Immigrants have traditionally

tended to place great emphasis on self-sacrifice, hard work, education,

community, and a willingness to strive for the general future betterment of

their families and communities—all things that have been in serious decline in

recent decades in

Somewhere late in this process, I read a wonderful new book

by Eric Lane and Michael Oreskes,

The Genius of America: How the Constitution

Saved Our Country and How It Can Again (Bloomsbury, New York,

2007). The “genius” it attributes to

In 1776, on the eve of independence

and war, Americans viewed themselves as capable of suppressing their individual

self-interest for the public good, in the conduct of their public affairs. They called this ability public virtue.

The reality set in. Not only was the War of Independence a time that “tried men’s souls,” in Paine’s memorable phrase; it also tested the faith that sound government could rest on public virtue, And faith in virtue failed. To be sure, the war had shown the extraordinary qualities of some Americans. But it had also demonstrated that Americans could be extraordinarily selfish. [p. 36]

The wartime deprivations had dramatized the weakness of a national government that rested on the belief that individual citizens and their states would be adequately motivated by public virtue to rally around national goals. [p. 38]

“We have probably had too good an

opinion of human nature in forming our confederation… We must take human nature

as we find it. Perfections falls not to the share of mortals,”

The authors concluded:

[the framers] had established an entirely new form of government based on new theories of government. They had, they thought, saved their country from chaos or tyranny.

They had developed a far more mature notion of public virtue, one which denied the possibility of—and, more important, eliminated the need for—perfection in human political behavior. In its place through representation and separation of powers, the framers substituted struggle among competing ideas, interests and egos. They no longer pretended they could fix human nature, so they harnessed it. Under this scheme the process would replace the product as the test of lawmaking legitimacy. “The founding fathers…saw conflict as the guarantee of freedom…The constitution thus institutionalized conflict in the very heart of the American polity. [p. 45]

After a beautiful presentation of the history of the framing and adopting of the Constitution, the authors go on to describe how this system and the “Constitutional conscience” that created and embraces it have functioned throughout the sweep of American history—requiring compromises and balances that imposed important correctives to the simple drift of majority rule. It describes the great historical challenges to these balances like the Sedition Act of 1798 and the Civil War—both, interestingly, moments when our Constitutional system was preserved by the efforts of the Republican party. The next great challenge came with the Great Depression; but, in the book’s view, FDR’s response to that, while it toyed with weakening the judiciary and succeeded in radically expanding the role of government in the life of the country beyond anything envisioned by the framers of the Constitution, continued powerfully to embrace and embody the Constitutional conscience in a way that continued to be true throughout the next three decades. The books sees the current breakdown of that Constitutional compromise having its precursors—but not its real dissolution-- in the presidency of Richard Nixon, and really starting to deteriorate thereafter, beginning with Jimmy Carter, but really gathering impetus under Ronald Reagan.

So, ultimately, the book is talking about a decline in the

way America has functioned over the same three decades as those about which I

had been ranting, albeit that the authors have what is a more sophisticated—but

not unrelated—notion of what has been going on in this decline. One way or the other, the balances that had

made democracy (and, according to me, free markets) so successful in

The authors of The Genius of America are calling for a return to those principles of the Constitutional conscience---most importantly including real discourse, meaningful interactions between the various factions of the polity and branches of the government, and respect for the Constitution itself.

Our new president-elect has monumental problems he will need to provide leadership in solving. We can only hope that this election and the shift in the spirit in the country will turn us back to a system that has functioned so well in the past. We are at an important potential moment of change: the youth of America have been engaged and active in a way our country has not seen in decades, the country has elected a thoughtful, intelligent leader—one with principles, but with an apparent desire for real discourse and meaningful compromise—and there seems to be a sea change in the air.

Let us hope that he and we have the strength and courage to pull it off. So much is hanging in the balance.

There’s far more I’d like to add, but if I don’t stop here,

I won’t get this off before leaving for the Urban Age conference in

Just a parting visual of the pedimental sculpture over east entrance to the U.S. Capitol—called “The Genius of America”—before I run off to catch my flight:

The sculptural pediment (by Italian

sculptor Luigi Persico ) over the east central entrance of the U.S. Capitol is

called Genius of America. The

central figure represents

The sculptural pediment (by Italian

sculptor Luigi Persico ) over the east central entrance of the U.S. Capitol is

called Genius of America. The

central figure represents

-The Architect of the Capitol (responsible to the

United States Congress for the maintenance, operation, development, and

preservation of the United States Capitol Complex, which includes the Capitol,

the congressional office buildings, the Library of Congress buildings, the

Supreme Court building, the U.S. Botanic Garden, the Capitol Power Plant, and

other facilities) www.aoc.gov/cc/art/pediments/gen_ctr.cfm?displaylargeimages=1

NOTES:

Some corrections about the Hebrew quotation, “Hazak hazak v’nithazek”:

1. The source of this phrase is Rabbinic; it is not actually found in the Bible in this form

2. Nevertheless, the repetition of the word “hazak” most assuredly is a an allusion to the first chapter of Joshua, in which it is repeated twice—at the beginning of verse 6, “hazah v’ematz” (חזק ואמץ), and again at the beginning of verse 7, “rak hazah v’ematz” (רק חזק ואמץ); it is actually reprised a third time in the middle of verse 9

3. The translation “be strong and of good courage” (or, simply, “be strong and courageous”) is of “hazah v’ematz” (חזק ואמץ)—and it is not, as I had suggested, an idiomatic rendering of “hazak v’nithazek” (חזק ונתחזק); and the “rak hazah v’ematz m’od” (מאד רק חזק ואמץ) of verse 7 is translated “only be strong and of very good courage”

4. The only time the phrase “hazak v’nithazek” (חזק ונתחזק) occurs in the Bible (and, actually, the only occurrence at all of the verbal form “nithazek” [hitpael first person plural imperfect of חזק—the hitpael usually being the reflexive form of that sort of verb, or a form that implies “making ourselves strong,” in this case) is in II Samuel 10:12

5. The translation I quoted, “Be strong, be strong. And let us strengthen one another,” is of “hazak v’nithazek” (חזק ונתחזק)

6. The phrase is said by some congregations at the completion of each of the five books of the Torah, by some only after the completion of all five…and in some after the completion of any book

Return to Dead Parrot homepage.